Building_structural Causal_models_with_dowhy_&_econml_gcm

End-to-End approach for building Causal Models using— DoWhy + EconML + Refutation Tests + GCM API

This notebook demonstrates the main ideas and libraries used in Chapter 7 of Molak:

- DoWhy: the 4-step causal workflow

- Step 1: encode assumptions (a causal graph)

- Step 2: identify the estimand (what needs to be computed)

- Step 3: estimate the effect (linear regression, Double ML)

- Step 4: refute the estimate (robustness / stress tests)

- EconML: using Double Machine Learning (DML) as a causal estimator

- DoWhy GCM API: building a structural causal model and generating counterfactuals

Dataset choice (public + offline)

To keep this notebook runnable without external downloads, we use sklearn.datasets.load_diabetes() (ships with scikit-learn).

We then simulate a treatment and an outcome so we know the true causal effect and can sanity-check the tooling.

Why simulate treatment/outcome?

- Real public datasets rarely contain true randomized treatment.

- Chapter 7’s goal is to learn the ecosystem + workflow.

0) Setup

We try to import dowhy and econml. If they are missing, install them.

If you are in a restricted environment without pip access, run this notebook where you can pip install.

import sys

import subprocess

def pip_install(pkg):

print(f"Installing: {pkg}")

subprocess.check_call([sys.executable, "-m", "pip", "install", "-q", pkg])

# Core deps

for pkg in ["dowhy", "econml", "scikit-learn", "pandas", "numpy", "matplotlib", "networkx"]:

try:

__import__(pkg.split("==")[0])

except Exception:

pip_install(pkg)

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Installing: dowhy

Installing: econml

Installing: scikit-learn

import warnings

from sklearn.exceptions import DataConversionWarning

warnings.simplefilter("ignore", DataConversionWarning)

1) Create a public dataset + simulate a causal story

We start with the Diabetes dataset covariates W.

Then we create:

- Treatment

X: depends on some covariates (confounding) - Outcome

Y: depends onX+ covariates

We choose a true causal effect of X → Y to be about 0.7 (like the chapter’s synthetic example).

from sklearn.datasets import load_diabetes

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

rng = np.random.default_rng(42)

data = load_diabetes(as_frame=True)

W = data.frame.copy()

# Standardize covariates so our simulation coefficients are stable

scaler = StandardScaler()

W_scaled = pd.DataFrame(scaler.fit_transform(W), columns=W.columns)

n = len(W_scaled)

# Simulate a confounder-like latent signal using observed covariates

u = rng.normal(0, 1, size=n)

# Treatment X depends on covariates (confounding)

# (Continuous treatment to match the chapter’s DML regression example)

X = (

0.6 * W_scaled["bmi"].to_numpy() +

0.3 * W_scaled["bp"].to_numpy() +

0.2 * W_scaled["s5"].to_numpy() +

0.3 * u +

rng.normal(0, 0.5, size=n)

)

TRUE_ATE = 0.7

# Outcome Y depends on X and covariates

Y = (

TRUE_ATE * X +

0.4 * W_scaled["bmi"].to_numpy() +

0.2 * W_scaled["age"].to_numpy() -

0.3 * W_scaled["s1"].to_numpy() +

0.2 * u +

rng.normal(0, 1.0, size=n)

)

df = W_scaled.copy()

df["X"] = X

df["Y"] = Y

df.head()

| age | sex | bmi | bp | s1 | s2 | s3 | s4 | s5 | s6 | target | X | Y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.800500 | 1.065488 | 1.297088 | 0.459841 | -0.929746 | -0.732065 | -0.912451 | -0.054499 | 0.418531 | -0.370989 | -0.014719 | 1.272287 | 0.816080 |

| 1 | -0.039567 | -0.938537 | -1.082180 | -0.553505 | -0.177624 | -0.402886 | 1.564414 | -0.830301 | -1.436589 | -1.938479 | -1.001659 | -0.754342 | -0.834617 |

| 2 | 1.793307 | 1.065488 | 0.934533 | -0.119214 | -0.958674 | -0.718897 | -0.680245 | -0.054499 | 0.060156 | -0.545154 | -0.144580 | 0.590729 | 2.828625 |

| 3 | -1.872441 | -0.938537 | -0.243771 | -0.770650 | 0.256292 | 0.525397 | -0.757647 | 0.721302 | 0.476983 | -0.196823 | 0.699513 | -0.738321 | -1.308935 |

| 4 | 0.113172 | -0.938537 | -0.764944 | 0.459841 | 0.082726 | 0.327890 | 0.171178 | -0.054499 | -0.672502 | -0.980568 | -0.222496 | -0.507214 | -3.555118 |

Quick sanity check

- If we run a naive regression of Y on X without controlling for confounders, it can be biased.

- If we control for the right covariates, we should recover something close to the true effect (~0.7).

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Naive

X_naive = sm.add_constant(df[["X"]])

naive = sm.OLS(df["Y"], X_naive).fit()

print("Naive OLS coef on X:", naive.params["X"])

# Adjusted (include a bunch of covariates)

controls = [c for c in df.columns if c not in ["X", "Y"]]

X_adj = sm.add_constant(df[["X"] + controls])

adj = sm.OLS(df["Y"], X_adj).fit()

print("Adjusted OLS coef on X:", adj.params["X"])

print("True effect:", TRUE_ATE)

Naive OLS coef on X: 1.027198098583941

Adjusted OLS coef on X: 0.9013676299101012

True effect: 0.7

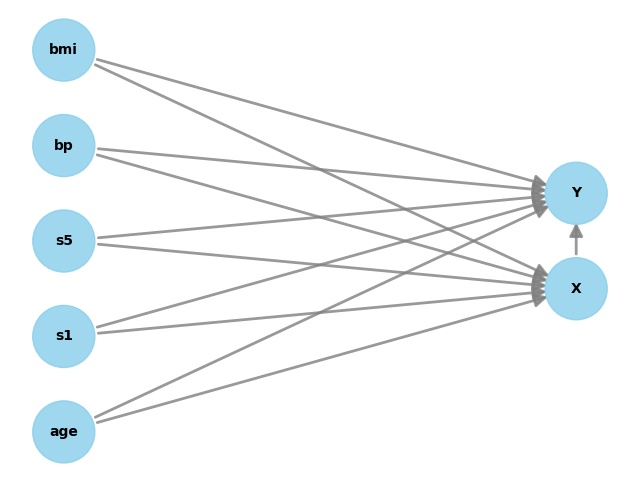

2) DoWhy Step 1 — Encode assumptions (DAG)

We now write a causal graph.

We’ll use a simple and realistic assumption:

- Several covariates W affect both X and Y (confounders)

- X affects Y

In DoWhy, you provide the graph as a string.

from dowhy import CausalModel

# We'll include a small subset of covariates to keep the graph readable.

confounders = ["bmi", "bp", "s5", "age", "s1"]

# Build a graph string (DOT format for DoWhy)

# Edges: confounders -> X and confounders -> Y, plus X -> Y

edges = []

for w in confounders:

edges.append(f"{w} -> X")

edges.append(f"{w} -> Y")

edges.append("X -> Y")

graph = "digraph {\n" + ";\n".join(edges) + ";\n}"

print(graph)

from dowhy import CausalModel

model = CausalModel(

data=df[["Y", "X"] + confounders],

treatment="X",

outcome="Y",

graph=graph

)

model.view_model()

digraph {

bmi -> X;

bmi -> Y;

bp -> X;

bp -> Y;

s5 -> X;

s5 -> Y;

age -> X;

age -> Y;

s1 -> X;

s1 -> Y;

X -> Y;

}

3) DoWhy Step 2 — Identify the estimand

Now DoWhy uses the graph to answer:

“What expression can I compute from data to get the causal effect of X on Y?”

Usually, you’ll see it choose a backdoor adjustment set (control variables).

estimand = model.identify_effect()

print(estimand)

Estimand type: EstimandType.NONPARAMETRIC_ATE

### Estimand : 1

Estimand name: backdoor

Estimand expression:

d

────(E[Y|age,s1,s5,bp,bmi])

d[X]

Estimand assumption 1, Unconfoundedness: If U→{X} and U→Y then P(Y|X,age,s1,s5,bp,bmi,U) = P(Y|X,age,s1,s5,bp,bmi)

### Estimand : 2

Estimand name: iv

No such variable(s) found!

### Estimand : 3

Estimand name: frontdoor

No such variable(s) found!

### Estimand : 4

Estimand name: general_adjustment

Estimand expression:

d

────(E[Y|age,s1,s5,bp,bmi])

d[X]

Estimand assumption 1, Unconfoundedness: If U→{X} and U→Y then P(Y|X,age,s1,s5,bp,bmi,U) = P(Y|X,age,s1,s5,bp,bmi)

4) DoWhy Step 3 — Estimate the effect

We estimate the causal effect using two estimators (like the chapter):

- Linear regression (simple baseline)

- Double ML (DML) via EconML (more flexible, ML-based)

We then compare results to the known true effect (~0.7).

# 4.1 Linear regression estimator inside DoWhy

estimate_lr = model.estimate_effect(

identified_estimand=estimand,

method_name="backdoor.linear_regression"

)

print("DoWhy Linear Regression ATE:", estimate_lr.value)

print("True effect:", TRUE_ATE)

DoWhy Linear Regression ATE: 0.8933354974909335

True effect: 0.7

# 4.2 Double ML estimator via EconML

# We'll use gradient boosting to model the nuisance functions

from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingRegressor

from sklearn.linear_model import LassoCV

estimate_dml = model.estimate_effect(

identified_estimand=estimand,

method_name="backdoor.econml.dml.DML",

method_params={

"init_params": {

"model_y": GradientBoostingRegressor(random_state=42),

"model_t": GradientBoostingRegressor(random_state=42),

"model_final": LassoCV(fit_intercept=False, random_state=42),

},

"fit_params": {}

}

)

print("DoWhy + EconML DML ATE:", estimate_dml.value)

print("True effect:", TRUE_ATE)

DoWhy + EconML DML ATE: 0.9479973316124858

True effect: 0.7

Interpretation

- If both estimates are close to ~0.7, our identification + estimation is behaving properly.

- In real projects, you don’t know the true effect — so you rely more on:

- refutation tests

- sensitivity checks

- domain validation

5) DoWhy Step 4 — Refute the estimate (robustness tests)

Refutation tests try to break your causal result.

We’ll run the same style of tests used in the chapter:

- Data subset refuter (invariant transformation)

- Random common cause (invariant transformation)

- Placebo treatment refuter (nullifying transformation)

Key idea:

- Invariant transformations should not change the estimate much.

- Nullifying transformations should make the effect go to ~0.

# We'll refute the DML estimate (you can also refute the linear one)

print("Original DML estimate:", estimate_dml.value)

Original DML estimate: 0.9479973316124858

# 5.1 Data subset refuter

refute_subset = model.refute_estimate(

estimand=estimand,

estimate=estimate_dml,

method_name="data_subset_refuter",

subset_fraction=0.4,

random_seed=42

)

print(refute_subset)

Refute: Use a subset of data

Estimated effect:0.9479973316124858

New effect:0.8400437564259516

p value:0.48

# 5.2 Random common cause

refute_random_cc = model.refute_estimate(

estimand=estimand,

estimate=estimate_dml,

method_name="random_common_cause",

random_seed=42

)

print(refute_random_cc)

Refute: Add a random common cause

Estimated effect:0.9479973316124858

New effect:0.8424992466817046

p value:0.08

# 5.3 Placebo treatment refuter

refute_placebo = model.refute_estimate(

estimand=estimand,

estimate=estimate_dml,

method_name="placebo_treatment_refuter",

placebo_type="permute",

random_seed=42

)

print(refute_placebo)

Refute: Use a Placebo Treatment

Estimated effect:0.9479973316124858

New effect:0.003774568832559745

p value:0.98

How to read refutation outputs

Typically you see:

- Estimated effect (original)

- New effect (after refutation)

- p-value for the difference

What you want:

- subset/common-cause: new effect ≈ old effect (difference not significant)

- placebo: new effect ≈ 0

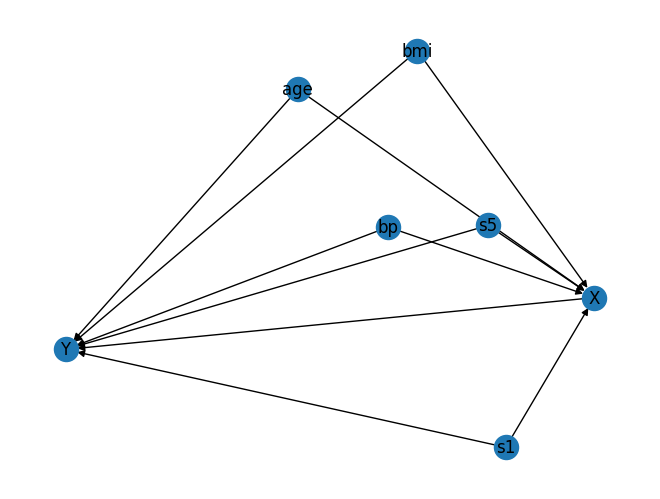

6) GCM API (extra) — structural causal modeling + counterfactuals

DoWhy’s GCM API lets you go beyond ATE and ask:

- “How strong are the incoming causal arrows into Y?”

- “What would Y have been if we set X to another value (counterfactual)?”

This requires specifying a causal mechanism for each node.

We’ll build a small graph with the same variables used above.

import networkx as nx

from dowhy import gcm

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

# Build the same causal structure using NetworkX

G = nx.DiGraph()

for w in confounders:

G.add_edge(w, "X")

G.add_edge(w, "Y")

G.add_edge("X", "Y")

# Plot (optional)

pos = nx.spring_layout(G, seed=42)

nx.draw(G, pos, with_labels=True)

plt.show()

from dowhy import gcm

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

from dowhy.gcm.ml import SklearnRegressionModel

# Create an invertible SCM (good for counterfactuals)

causal_model = gcm.InvertibleStructuralCausalModel(G)

# Root nodes as empirical distributions

for w in confounders:

causal_model.set_causal_mechanism(w, gcm.EmpiricalDistribution())

# X and Y as additive noise models with wrapped sklearn regressors

causal_model.set_causal_mechanism("X", gcm.AdditiveNoiseModel(SklearnRegressionModel(LinearRegression())))

causal_model.set_causal_mechanism("Y", gcm.AdditiveNoiseModel(SklearnRegressionModel(LinearRegression())))

# Fit mechanisms to data

gcm.fit(causal_model, df[["X", "Y"] + confounders])

print("GCM fitted.")

Fitting causal mechanism of node s1: 100%|██████████████████████████████████████████████| 7/7 [00:00<00:00, 282.99it/s]

GCM fitted.

6.1 Arrow strength into Y

This gives a measure of how much each parent contributes to explaining Y. This is not exactly the same as ATE. It’s more like: “How important is this causal parent in the model for Y?”

strengths = gcm.arrow_strength(causal_model, "Y")

strengths

{('X', 'Y'): np.float64(0.7045566616574985),

('age', 'Y'): np.float64(0.04788431176770035),

('bmi', 'Y'): np.float64(0.15649327627968032),

('bp', 'Y'): np.float64(0.01957459130750313),

('s1', 'Y'): np.float64(0.08355406661605072),

('s5', 'Y'): np.float64(0.009460206774970321)}

6.2 Counterfactual example

Counterfactual question:

For a specific observation, what would Y be if we forced X to some value?

We pick one row and set X to a new value.

row = df[["X", "Y"] + confounders].iloc[[0]].copy()

row

| X | Y | bmi | bp | s5 | age | s1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.272287 | 0.81608 | 1.297088 | 0.459841 | 0.418531 | 0.8005 | -0.929746 |

# Force X to a new value (intervention)

new_x = float(row["X"].iloc[0] - 1.0) # just as an example

cf = gcm.counterfactual_samples(

causal_model,

interventions={"X": lambda _: new_x},

observed_data=row

)

print("Observed:")

print(row[["X", "Y"] + confounders])

print("Counterfactual (X forced to new value):")

print(cf[["X", "Y"] + confounders])

Observed:

X Y bmi bp s5 age s1

0 1.272287 0.81608 1.297088 0.459841 0.418531 0.8005 -0.929746

Counterfactual (X forced to new value):

X Y bmi bp s5 age s1

0 0.272287 -0.077256 1.297088 0.459841 0.418531 0.8005 -0.929746

7) What you should take away (Chapter 7 in one page)

- DoWhy gives you a clean 4-step causal workflow: 1) graph → 2) estimand → 3) estimate → 4) refute

- EconML lets you plug in modern estimators like DML when you need ML flexibility.

- Refutation tests are your “validation set” for causal claims (they try to break the result).

- GCM lets you move into structural models and ask counterfactual questions.

Practical advice

In real marketing/personalization work, a solid minimum deliverable is:

- DAG + explanation of assumptions

- at least one backdoor estimator (linear or DML)

- refutation suite (subset, placebo, random common cause)

- sensitivity check (if possible)