Inverse_propensity_weighting_&_doubly_robust_estimation

Propensity Scores in Practice

A fully commented, marketing-focused notebook

Goal of this notebook

This notebook is designed to teach Chapter 5 of Matheus Facure – Causal Inference in Python, not just run code.

You will see:

- Why naive analysis is biased

- How propensity scores fix selection bias

- When IPW breaks

- Why Doubly Robust (DR) is safer

- How Double Machine Learning fits conceptually

- How to explain results to business / MRM stakeholders

We use a public marketing dataset (Hillstrom email campaign) so the ideas map directly to real-world marketing analytics

📊 Hillstrom (MineThatData) Email Marketing Dataset

Direct download (CSV): https://raw.githubusercontent.com/W-Tran/uplift-modelling/master/data/hillstrom/Kevin_Hillstrom_MineThatData_E-MailAnalytics_DataMiningChallenge_2008.03.20.csv

You can:

Open this link directly in a browser

Or use it in Python with pd.read_csv(url)

🔗 Original source (background & documentation)

MineThatData – Email Analytics Challenge (Kevin Hillstrom): https://www.minethatdata.com/data-mining-challenge/

Big Picture (context)

We want to answer a causal question:

Does sending a marketing email cause higher customer spend / conversion?

This is not the same as:

“Do customers who receive emails spend more?”

Why?

- Marketing emails are not sent at random

- Better / more engaged customers are more likely to be targeted

- That creates selection bias

Chapter 5 is about how to remove that bias.

Methods we will compare

We will implement and compare four approaches:

- Naive regression – shows the bias

- IPW (Inverse Propensity Weighting) – design-based correction

- Outcome regression – model-based correction

- Doubly Robust (AIPW) – combines both

- Conceptual Double ML – how DR extends to ML safely

For each method, we answer:

- What assumption does it rely on?

- When does it work?

- When does it fail?

Dataset: Hillstrom Email Marketing (Public)

This dataset comes from a well-known marketing challenge.

Interpretation of columns

- Each row = one customer

segment= which email (if any) the customer received- Customer attributes = recency, history, channel, etc.

- Outcomes = spend and conversion

Treatment definition

T = 1→ customer received any emailT = 0→ customer received no email

This mirrors real-world campaign targeting.

# === Standard imports ===

# We keep models simple and interpretable on purpose.

# Chapter 5 is about *causality*, not model tuning.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.compose import ColumnTransformer

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression, LinearRegression

from sklearn.metrics import roc_auc_score

np.random.seed(42)

# === Load the Hillstrom dataset (public) ===

# If this fails due to network restrictions, download the CSV manually

# and set DATA_PATH accordingly.

import pathlib, urllib.request

DATA_DIR = pathlib.Path("data")

DATA_DIR.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

DATA_PATH = DATA_DIR / "hillstrom.csv"

URL = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/W-Tran/uplift-modelling/master/data/hillstrom/Kevin_Hillstrom_MineThatData_E-MailAnalytics_DataMiningChallenge_2008.03.20.csv"

if not DATA_PATH.exists():

urllib.request.urlretrieve(URL, DATA_PATH)

df = pd.read_csv(DATA_PATH)

df.head()

| recency | history_segment | history | mens | womens | zip_code | newbie | channel | segment | visit | conversion | spend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 2) $100 - $200 | 142.44 | 1 | 0 | Surburban | 0 | Phone | Womens E-Mail | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 6 | 3) $200 - $350 | 329.08 | 1 | 1 | Rural | 1 | Web | No E-Mail | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 7 | 2) $100 - $200 | 180.65 | 0 | 1 | Surburban | 1 | Web | Womens E-Mail | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 9 | 5) $500 - $750 | 675.83 | 1 | 0 | Rural | 1 | Web | Mens E-Mail | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 4 | 2 | 1) $0 - $100 | 45.34 | 1 | 0 | Urban | 0 | Web | Womens E-Mail | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

# === Define treatment, outcome, and covariates ===

df = df.copy()

# Treatment: received any email vs none

df["T"] = (df["segment"].str.lower() != "no e-mail").astype(int)

# Outcomes

df["Y_spend"] = df["spend"].astype(float)

df["Y_conv"] = df["conversion"].astype(int)

# Covariates (chosen to reflect realistic marketing features)

covariates = [

"recency", "history", "history_segment",

"mens", "womens", "zip_code", "newbie", "channel"

]

df[covariates + ["T", "Y_spend", "Y_conv"]].head()

| recency | history | history_segment | mens | womens | zip_code | newbie | channel | T | Y_spend | Y_conv | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 142.44 | 2) $100 - $200 | 1 | 0 | Surburban | 0 | Phone | 1 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1 | 6 | 329.08 | 3) $200 - $350 | 1 | 1 | Rural | 1 | Web | 0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 2 | 7 | 180.65 | 2) $100 - $200 | 0 | 1 | Surburban | 1 | Web | 1 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 3 | 9 | 675.83 | 5) $500 - $750 | 1 | 0 | Rural | 1 | Web | 1 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 4 | 2 | 45.34 | 1) $0 - $100 | 1 | 0 | Urban | 0 | Web | 1 | 0.0 | 0 |

Step 1 — Why naive analysis fails

We start with the wrong approach on purpose.

If we simply compare:

- average spend of emailed customers

- vs non-emailed customers

we are implicitly assuming random assignment.

That assumption is false in observational marketing data.

👉 This step is crucial for storytelling:

it shows stakeholders why causal methods are needed.

# === Naive comparison (intentionally biased) ===

naive_spend = df.groupby("T")["Y_spend"].mean()

naive_conv = df.groupby("T")["Y_conv"].mean()

print("Naive spend difference:", naive_spend[1] - naive_spend[0])

print("Naive conversion difference:", naive_conv[1] - naive_conv[0])

# Interpretation:

# This looks like a treatment effect,

# but it mixes true causal impact with selection bias.

Naive spend difference: 0.5967960667278982

Naive conversion difference: 0.004954571155268468

Step 2 — Propensity Scores (the key idea of Chapter 5)

The propensity score is:

[ e(X) = P(T=1 | X) ]

Plain English:

“Given what we know about a customer, how likely were they to be emailed?”

Why this matters:

- Customers with the same propensity score are comparable

- Conditioning on the propensity score balances all covariates

This is the foundation of IPW and DR.

# === Propensity score model ===

X = df[covariates]

T = df["T"].values

num_cols = [c for c in covariates if pd.api.types.is_numeric_dtype(df[c])]

cat_cols = [c for c in covariates if c not in num_cols]

preprocess = ColumnTransformer(

[

("num", "passthrough", num_cols),

("cat", OneHotEncoder(handle_unknown="ignore"), cat_cols),

]

)

ps_model = Pipeline(

[

("prep", preprocess),

("logit", LogisticRegression(max_iter=2000)),

]

)

X_train, X_test, T_train, T_test = train_test_split(

X, T, test_size=0.3, stratify=T, random_state=42

)

ps_model.fit(X_train, T_train)

e_hat = ps_model.predict_proba(X_test)[:, 1]

print("Propensity AUC:", roc_auc_score(T_test, e_hat))

Propensity AUC: 0.49176685713090773

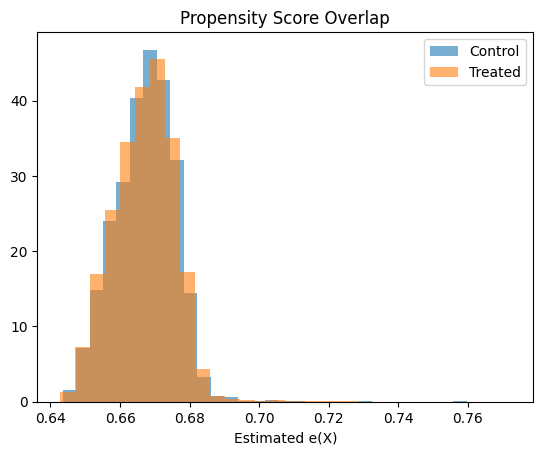

# === Overlap / positivity check ===

plt.hist(e_hat[T_test == 0], bins=30, alpha=0.6, label="Control", density=True)

plt.hist(e_hat[T_test == 1], bins=30, alpha=0.6, label="Treated", density=True)

plt.legend()

plt.title("Propensity Score Overlap")

plt.xlabel("Estimated e(X)")

plt.show()

# Interpretation:

# Good overlap → IPW is feasible

# Poor overlap → expect unstable weights

Step 3 — IPW (Inverse Propensity Weighting)

Core idea

Instead of changing the model, we change the importance of observations.

- Customers who were unlikely to be emailed but were emailed → get large weight

- Customers who were very likely to be emailed → get small weight

This creates a pseudo-randomized dataset.

Key assumption

- The propensity model is correct

# === IPW estimator ===

def ipw_ate(y, t, e, stabilized=False):

eps = 1e-6

e = np.clip(e, eps, 1 - eps)

if stabilized:

p = t.mean()

w = np.where(t == 1, p / e, (1 - p) / (1 - e))

else:

w = np.where(t == 1, 1 / e, 1 / (1 - e))

ate = (

np.sum(w[t == 1] * y[t == 1]) / np.sum(w[t == 1])

- np.sum(w[t == 0] * y[t == 0]) / np.sum(w[t == 0])

)

return ate, w

Y = df.loc[X_test.index, "Y_spend"].values

ate_ipw, w_raw = ipw_ate(Y, T_test, e_hat, stabilized=False)

ate_ipw_stab, w_stab = ipw_ate(Y, T_test, e_hat, stabilized=True)

print("IPW ATE:", ate_ipw)

print("Stabilized IPW ATE:", ate_ipw_stab)

IPW ATE: 0.6869934772562071

Stabilized IPW ATE: 0.6869934772562072

Step 4 — Why IPW can be dangerous

IPW can fail badly when:

- Some customers have propensity scores near 0 or 1

- Weights explode

- A few customers dominate the estimate

We will:

- Inspect weight distributions

- Compute effective sample size (ESS)

- Apply stabilization and clipping

This is mandatory in real work.

# === Weight diagnostics ===

def ess(w):

return (w.sum() ** 2) / (w ** 2).sum()

print("Max raw weight:", w_raw.max())

print("ESS raw:", ess(w_raw))

print("ESS stabilized:", ess(w_stab))

# Interpretation:

# Stabilization usually increases ESS dramatically

Max raw weight: 4.160191208753913

ESS raw: 17043.204198395597

ESS stabilized: 19193.43392200713

Step 5 — Doubly Robust Estimation (AIPW)

This is the main takeaway of Chapter 5.

Doubly Robust combines:

- A propensity model (design-based)

- An outcome model (model-based)

Why it’s powerful

- If either model is correct → estimate is consistent

- You get two chances to be right

This is why DR is the default choice in practice.

# === Outcome regression ===

outcome_model = Pipeline(

[

("prep", preprocess),

("lr", LinearRegression()),

]

)

outcome_model.fit(

pd.concat([X_train, pd.Series(T_train,index=X_train.index, name="T")], axis=1),

df.loc[X_train.index, "Y_spend"],

)

# Simpler demonstration:

# Separate models by treatment group

m1 = LinearRegression().fit(

preprocess.fit_transform(X_train[T_train == 1]),

df.loc[X_train.index[T_train == 1], "Y_spend"]

)

m0 = LinearRegression().fit(

preprocess.fit_transform(X_train[T_train == 0]),

df.loc[X_train.index[T_train == 0], "Y_spend"]

)

m1_hat = m1.predict(preprocess.transform(X_test))

m0_hat = m0.predict(preprocess.transform(X_test))

ate_or = (m1_hat - m0_hat).mean()

print("Outcome regression ATE:", ate_or)

Outcome regression ATE: 0.5598623633614704

# === Doubly Robust / AIPW ===

def aipw_ate(y, t, e, m0, m1):

eps = 1e-6

e = np.clip(e, eps, 1 - eps)

return np.mean(

(m1 - m0)

+ t * (y - m1) / e

- (1 - t) * (y - m0) / (1 - e)

)

ate_dr = aipw_ate(Y, T_test, e_hat, m0_hat, m1_hat)

print("Doubly Robust ATE:", ate_dr)

# Interpretation:

# If either the propensity model OR outcome model is correct,

# this estimate is consistent.

Doubly Robust ATE: 0.6886373812888652

Step 6 — Where Double Machine Learning fits

Double ML builds on DR ideas but adds:

- Cross-fitting

- Orthogonalization

- Safe use of ML models

Conceptually:

- DR = robustness to misspecification

- Double ML = robustness + protection against ML overfitting

We explain this conceptually (implementation is similar but heavier).

Final Summary (what to remember)

- Regression trusts the outcome model

- IPW trusts the assignment mechanism

- DR trusts either one

- Double ML lets you use ML safely

In observational marketing data:

Doubly Robust is almost always the right baseline choice.